Reasons for Revision

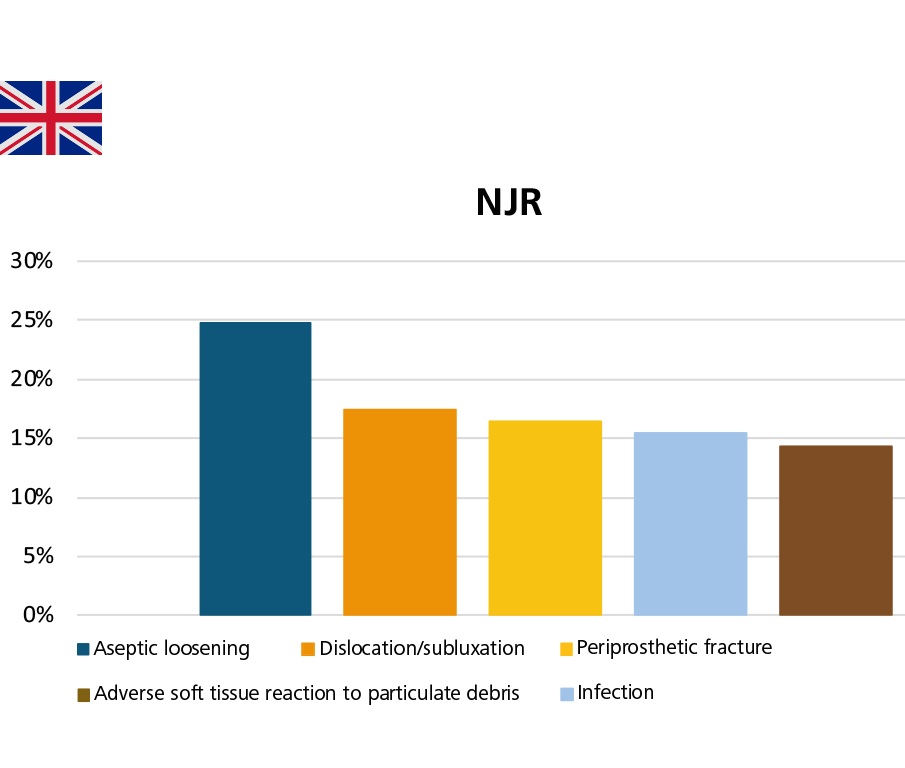

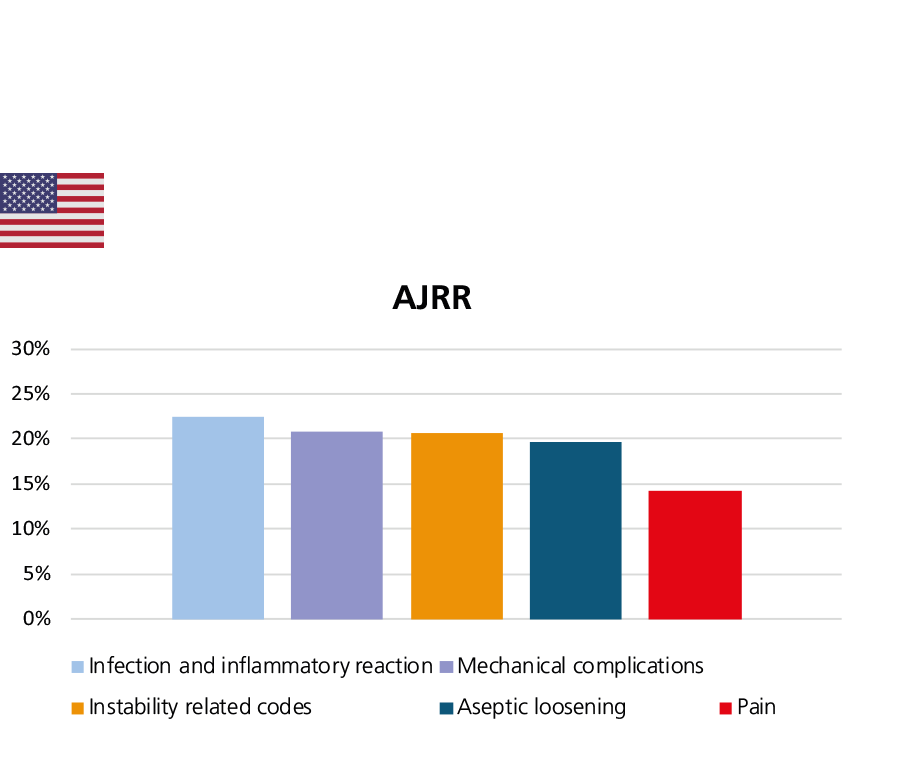

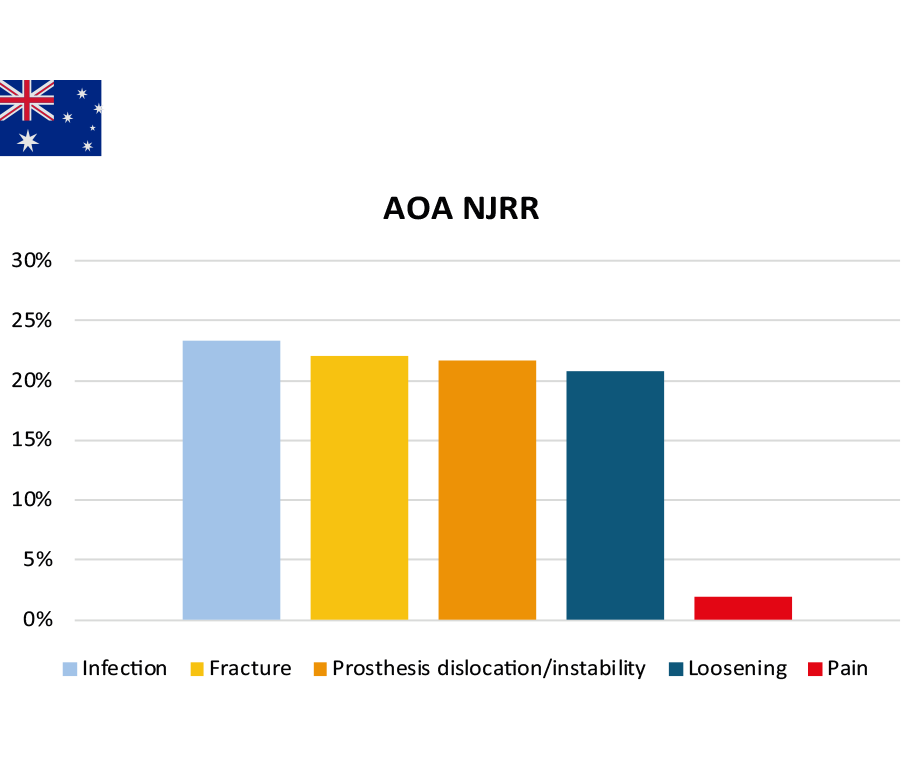

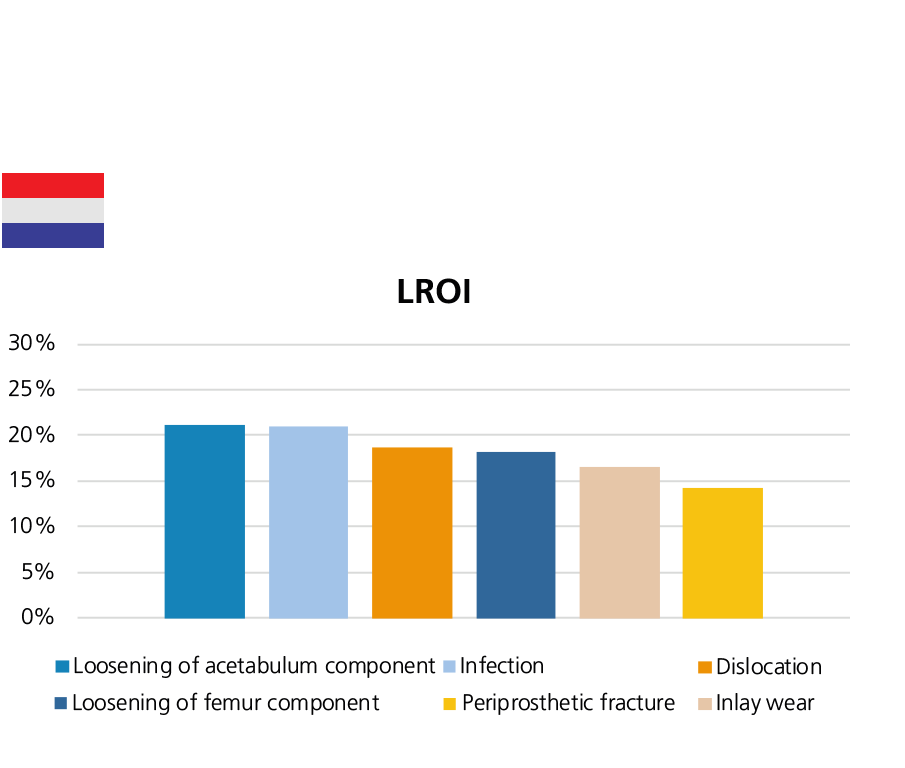

With regard to the most common reasons for revision, the terminologies used in the national registries varies slightly. There are also some differences between countries in the ordering of the main reasons. (Aseptic) loosening, infection, dislocation and (periprosthetic) fractures were at the top of the list, although with the order varied.

In 2022, infection (23.3%) is the most common reason for revision for all primary conventional THRs with primary diagnosis osteoarthritis (OA), followed by (periprosthetic) fracture (22.0%), prosthesis dislocation/instability (21.7%), and loosening (20.8%).

In 2022, the Australian registry conducted a comprehensive analysis of infections following primary hip, knee and shoulder replacements. The key messages on infections in hip replacement include:

- The number of revision procedures due to infection increased from 1.3% (333 revisions) of all hip surgeries in 2003 to 2.2% (1,173 revisions) in 2022. In contrast, all hip revisions for reasons other than infection decreased from 11.7% (3,111 revisions) in 2003 to 5.1% (2,690) in 2022.

- Across all age groups, revisions for infection are more common in males, while revisions for reasons other than infection are more common in females.

- For primary total conventional hip replacement with a primary diagnosis OA, the mean time to first revision due to infection is shorter than the mean time to first revision for reasons other than infection (1.8 ± 3.1 years versus 3.7 ± 4.4 years post primary procedure).

- For primary total conventional hip replacement with primary diagnosis OA, of all first revision for infection, 45.2% (1,515 procedures) of all first revisions for infection were metal/XLPE, followed by ceramic/XLPE (28.9%, 968 procedures), then ceramic/ceramic (12.6%, 422 procedures), and lastly ceramicised metal/XLPE (7.4%, 248 procedures). Of all first revision surgeries performed for other reasons, 42.4% (4,684 procedures) were metal/XLPE, 21.6% (2,387 procedures) were ceramic/XLPE, then ceramic/ceramic (18.7%, 2,065), and finally ceramicised metal/XLPE (7.1%, 781 procedures).

- When primary hip replacements are revised due to infection, 51.1% are due to early revisions, which the AOA NJRR defined as a revision within 3 months post primary procedure. Specifically, 24.1% occurs between 7 days and 4 weeks after primary procedure, 26.6% are revised in the period between 4 weeks and 3 months after primary procedure, 25.5% happens after 2 years.

- After first revision for infection, a risk of second revision for any reason is as high as 45.3% at 10 years.2

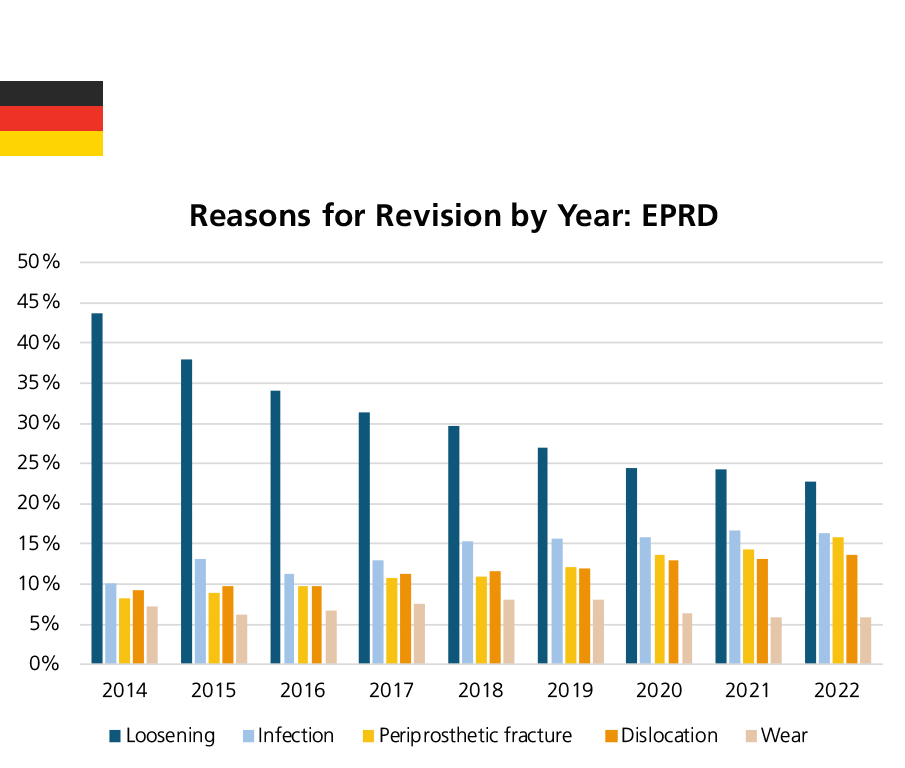

EPRD still provides data on reasons for revision based on procedures performed in the operation year. In 2022, loosening (22.7%), infection (16.4%), periprosthetic fracture (15.9%), dislocation (13.6%), and implant wear (5.8%) were the most common reasons for revision. Revision rates for loosening decreased each year, from 43.7% in 2014 to 22.7% in 2022. In contrast, revision rates due to infection increased from 10.1% in 2014 to 16.4% in 2022.3

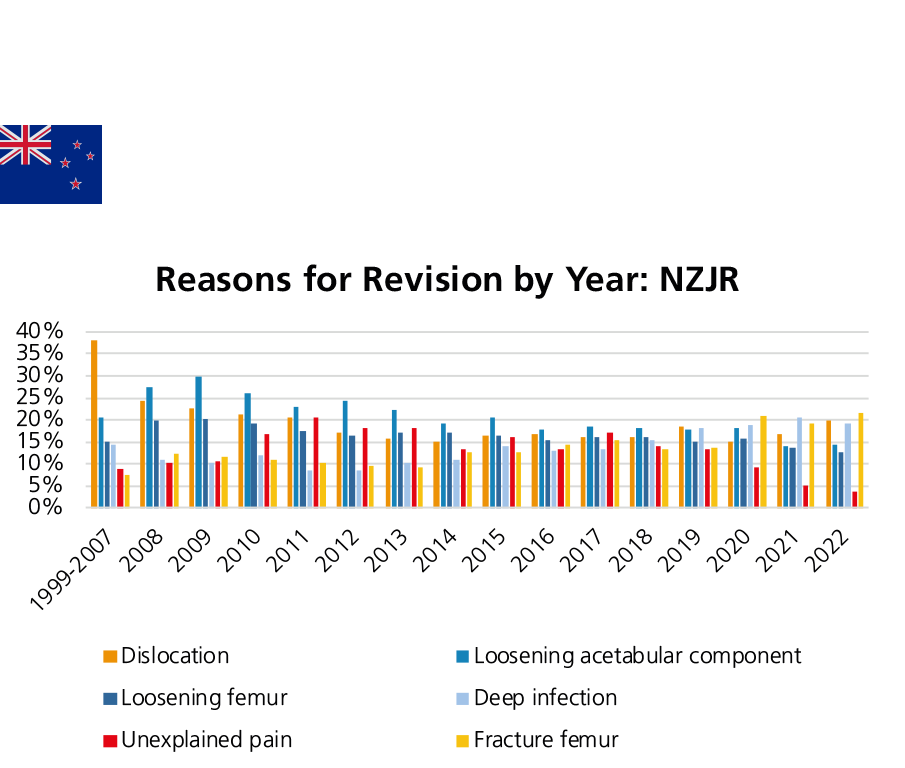

Since 1999, the six main reasons for revision after THR procedures in New Zealand are: loosening (of the acetabular and femoral component, respectively), dislocation/instability, unexplained pain, deep infection, and fracture femur. Deep infection and dislocation are more often happened within the first year after operation. On the other hand, loosening is a more common indication for revision beyond 10 years after operation.5

The most common reasons for revision surgery in the period 2020 to 2022 were: loosening, infection, peri-prosthetic fracture, and dislocation/instability. The percentage of revisions due to loosening has decreased, while the percentage of infection has increased. A high number of revisions due to pseudotumors (ALVAL, Aseptic Lymphocyte-dominated Vasculitis-Associated Lesions or ALTR, Adverse Local Tissue Reaction belong to this category acc. to the registry report) was noted especially at the beginning of the period from 2014 to 2016, then decreased significantly thereafter. Ten cases were reported in 2022.6

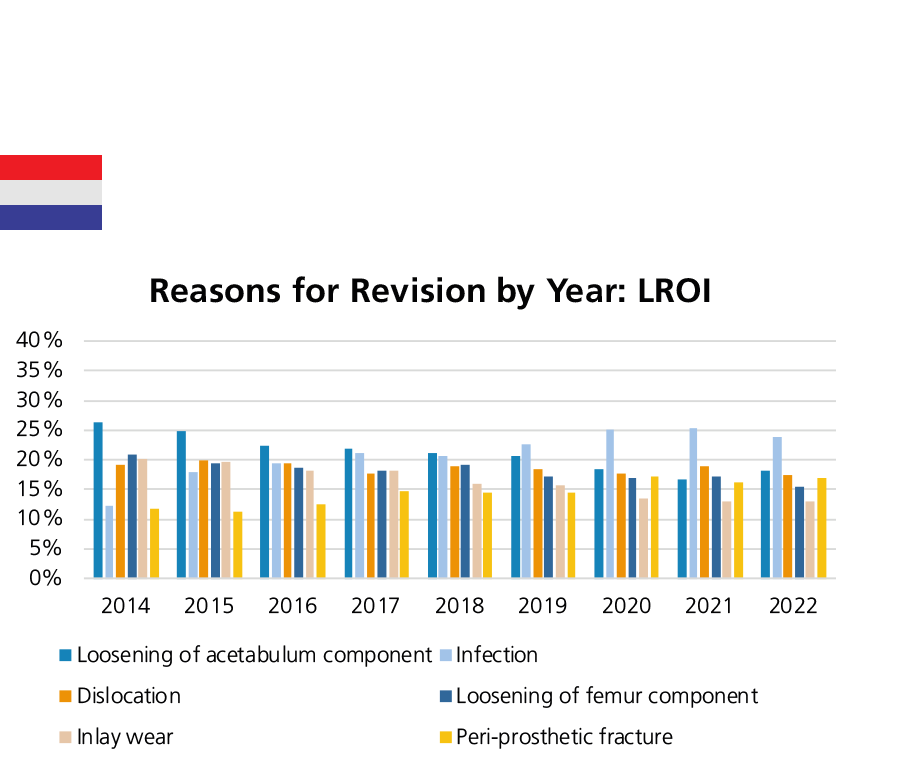

The most common reasons for revision recorded by LROI of all revision procedures between 2014 and 2022 were loosening of acetabulum component (21.2%), infection (20.9%), dislocation (18.6%), loosening of femur component (18.2%), and inlay wear (16.5%). The annual revision for infection increased from 12.3% in 2014 to 23.9% in 2022.7

Figure 12: The most common reasons for revision in England, Wales, Northern Ireland, the Isle of Man and Guernsey, Australia, the United States and the Netherlands.

Evaluation of the data by CeramTec based on the NJR Annual Report 2023 Page 106, the reasons for revision recorded in the NJR are not mutually exclusive. AOA NJRR Annual Report 2023 Page 118 Table HT15, and AJRR Annual Report 2023 Page 56 Figure 2.32, LROI Annual Report 2023 Page 34 Figure Reasons for revision.

Trends in Reasons for Revision

In Annual Report 2023, EPRD shows the following developments in the percentage shares of various treatment characteristics in primary THRs from 2012/13 to 2022, such as: fixation, insert materials, head sizes, head neck length as well as reasons for revision. As shown in the EPRD, revision rate due to loosening is decreasing each year. The revisions due to infection increased from 10.1% in 2014 to 16.4% in 2022. Similarly, the revision rates due to infections documented by the AJRR varies from 10.9% to 22.6% between 2012 and 2020, and then stabilized at about 23% in 2021 and 2022 (AJRR Annual Report 2023 Page 58 Figure 2.35). In the Netherlands, the annual revision for infection increased from 12.3% in 2014 to 25.3% in 2021 and then declined slightly to 23.9% in 2022. The NZJR has also provided insight into the year-on-year trends of their six main reasons for revision. The revision rate due to deep infection increased from 8.6% in 2012 to 19.3% in 2022. The revision rate due to fracture femur has steadily increased from 9.3% in 2013 to 21.5% in 2022. On the other hand, the revision rate due to unexplained pain declined from a peak of 20.6% in 2011 to 9.4% in 2020, then to the lowest point recorded in the registry in almost a decade, namely 3.6% in 2022.

By the end of 2022, the NJR has recorded a total of 1,448,541 primary hip replacements over the lifetime of the registry, of which 43,682 (3%) were linked first revisions. It can be observed that the number of revisions increased each year from 2003 to 2008 and decreased each year from 2008 to 2022. The NJR is reporting a maximum of 19.75 years of follow-up.

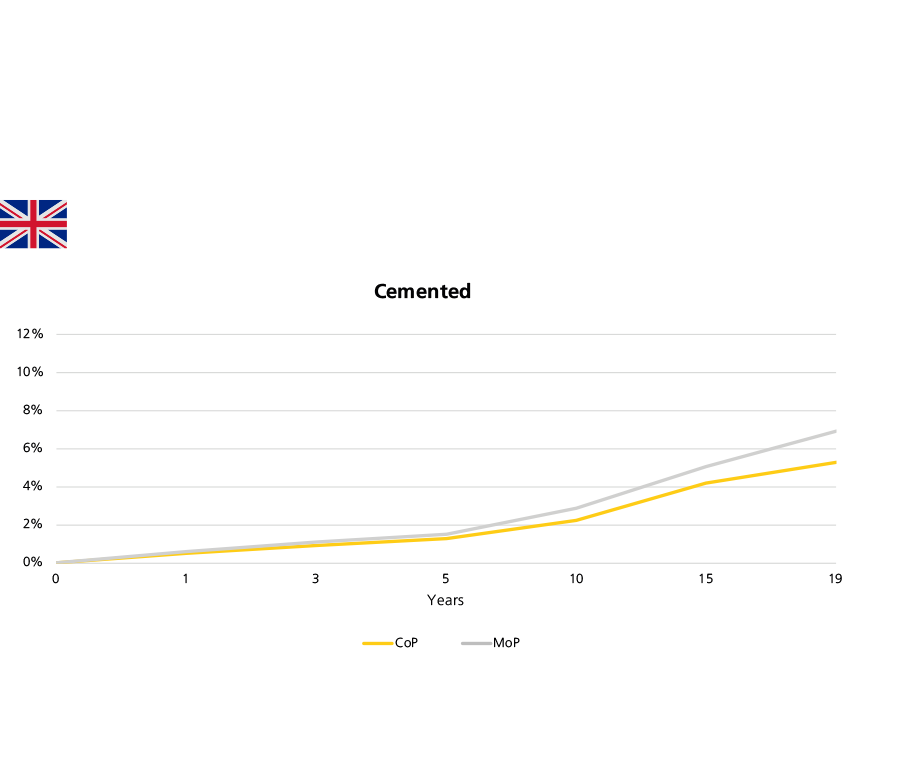

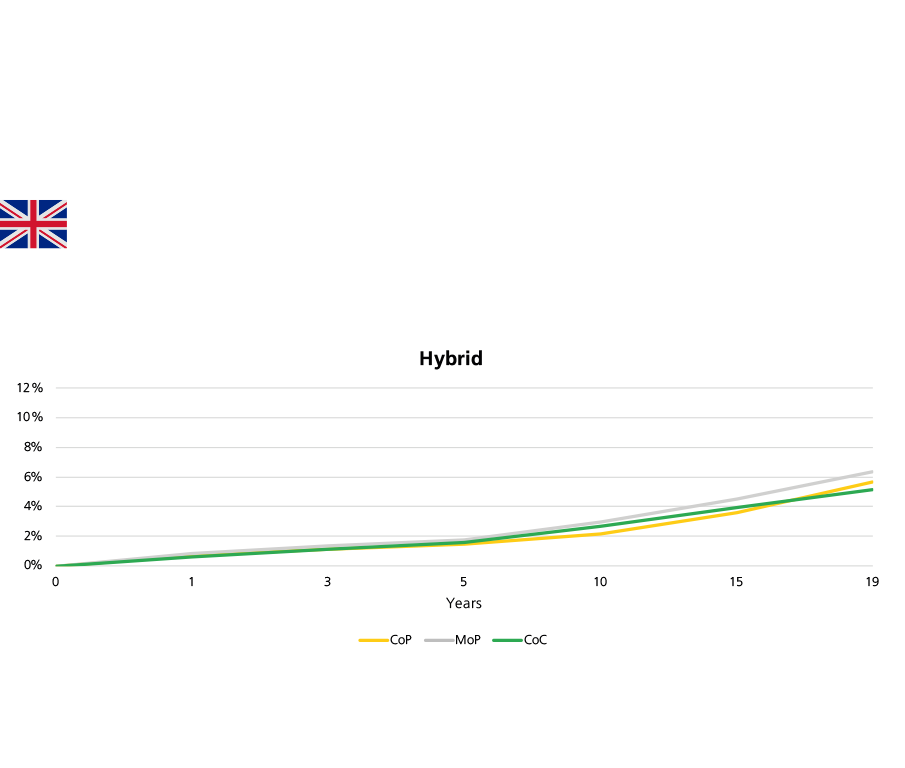

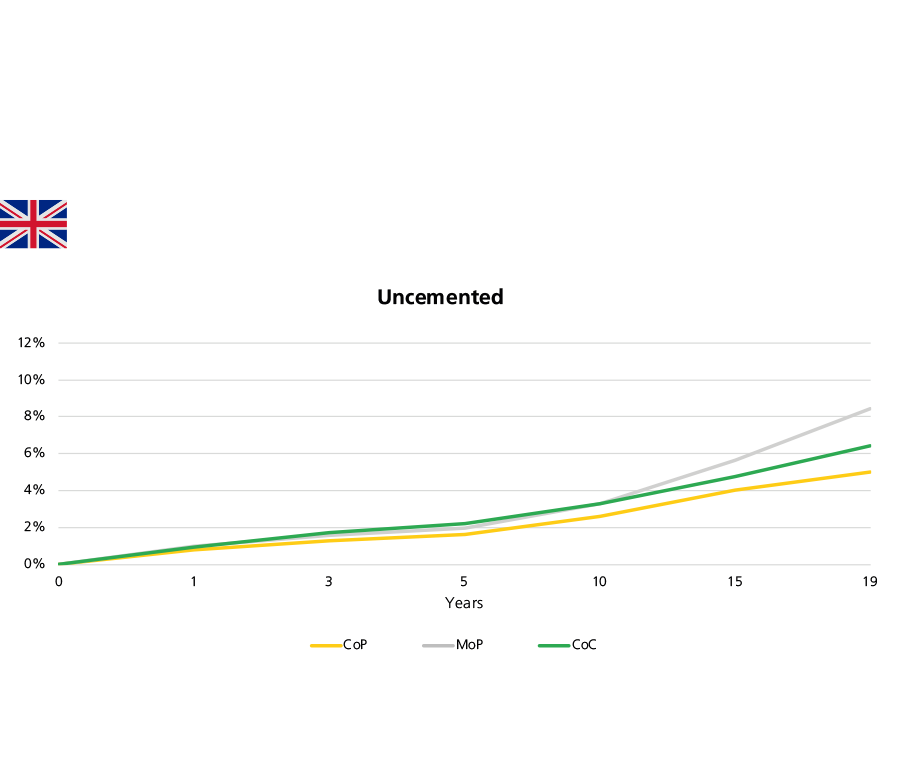

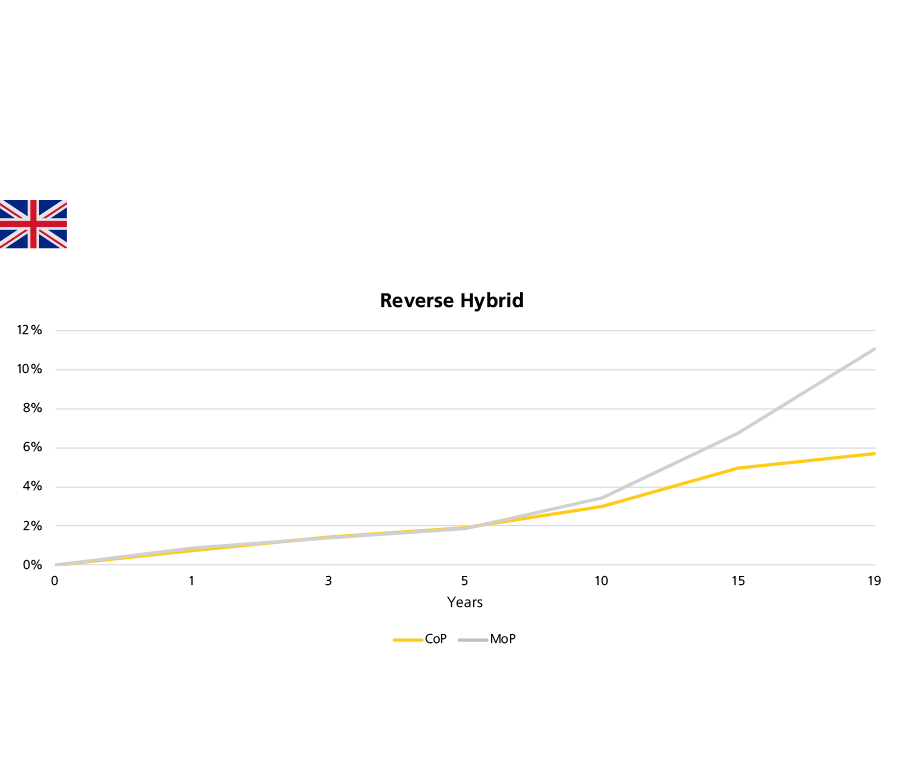

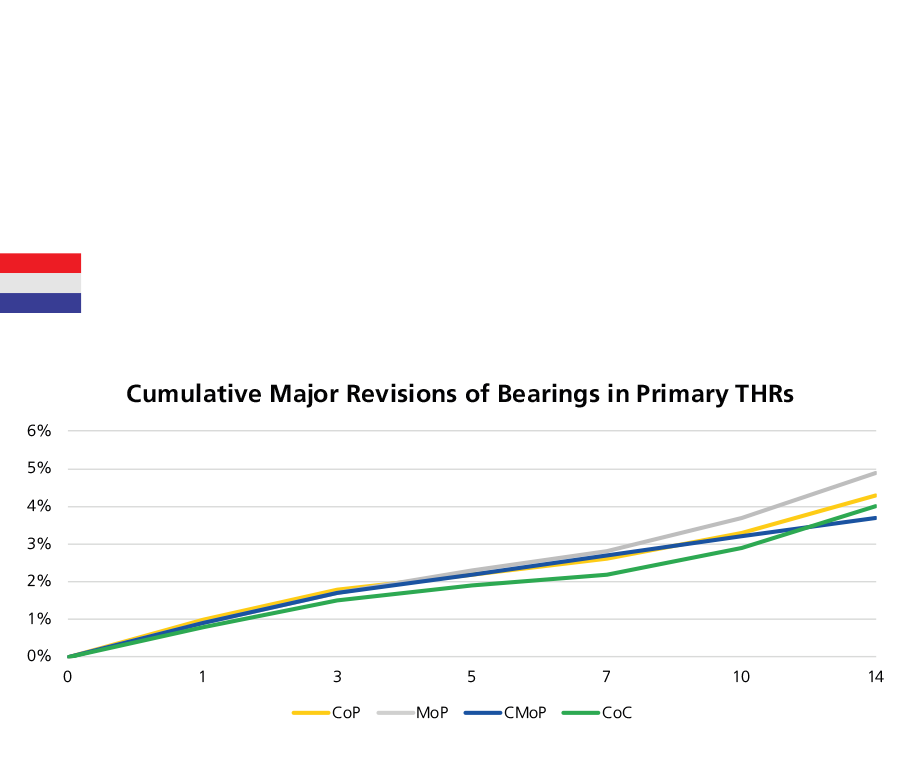

Across all fixation methods, CoP bearings have consistently maintained a low or similar rate of revision to those of other bearings up to fifteen years. The excellent results encourage wider use of CoP bearings.

As the number of cases recorded by NJR increases, the confidence intervals narrow and statistical significance is reached for both genders, all age groups, and up to 18 years after implantation. This year, the results obtained in younger patients by CoC and CoP are statistically better than those obtained by MoP; the NJR 2023 Annual Report states that these results are “striking”. For male patients aged 55 to 64 years, CoP and CoC with hybrid fixation, CoP and CoC with uncemented fixation, as well as cemented CoP bearings have relatively low revision rates, about below 5% at 15 years postoperatively. In contract, the revision rate of cemented MoP bearings and uncemented MoP were 8.26% and 7.06%, respectively. For female patients aged 55 to 64 years old, the revision rates of hybrid CoC was 3.05% (95% CI 2.58%-3.59%) at 15 years.

As shown in Figure 16, in the cemented fixation group, CoP bearings with 36mm heads had higher revision rates than those with 28- and 32mm heads. Correspondingly, in the uncemented and hybrid fixation groups, CoP bearings with 32- and 36mm heads had lower revision rates than 28mm heads.

In the uncemented fixation group, there is a clear correlation between the revision rates of CoC bearings and head size: the larger the head, the lower the revision rate of the construct (except for 44mm heads after six years). In the hybrid fixation group, the revision rate of CoC bearings with 36mm heads was higher than that of 32- and 28mm heads (p=0.001).This annual report indicates that the early failure rate of MoPoM in uncemented and hybrid group were higher than most bearings. At this point, CoPoM performs better but with a small number.

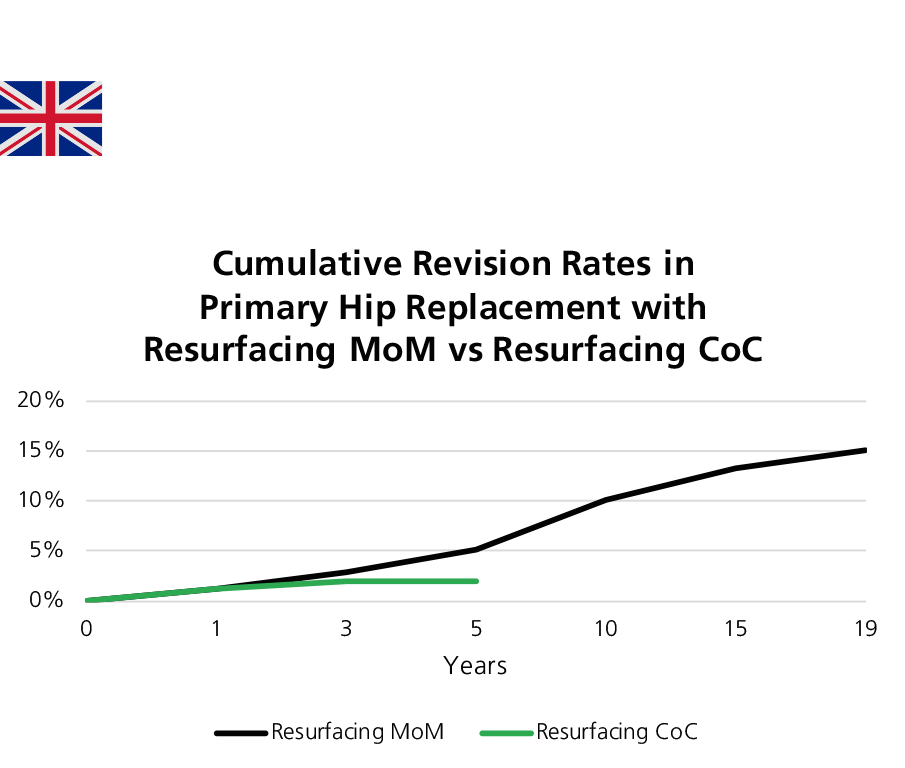

CoC resurfacing is recorded by the NJR for the first time in 2022, although this construct is still undertaken in small numbers (N=249). The early revision rate at 1 year for CoC resurfacing is similar to that for MoM resurfacing (1.27% (0.41%-3.87%) vs. 1.18% (1.08%-1.29%)), and lower at 3 years (1.91% (0.71%-5.11%) vs. 2.90 (2.74%-3.06%)) and 5 years (1.91% (0.71%-5.11%) vs. 5.06% (4.85%-5.28%)). The NJR reminds readers to be cautious in interpreting this difference due to the small number of CoC resurfacing.

(Figure 17)

According to AOA NJRR Annual Report 2023, the 20-year cumulative revision rate of all primary total conventional hip replacement procedures with primary diagnosis OA is 8.1%.

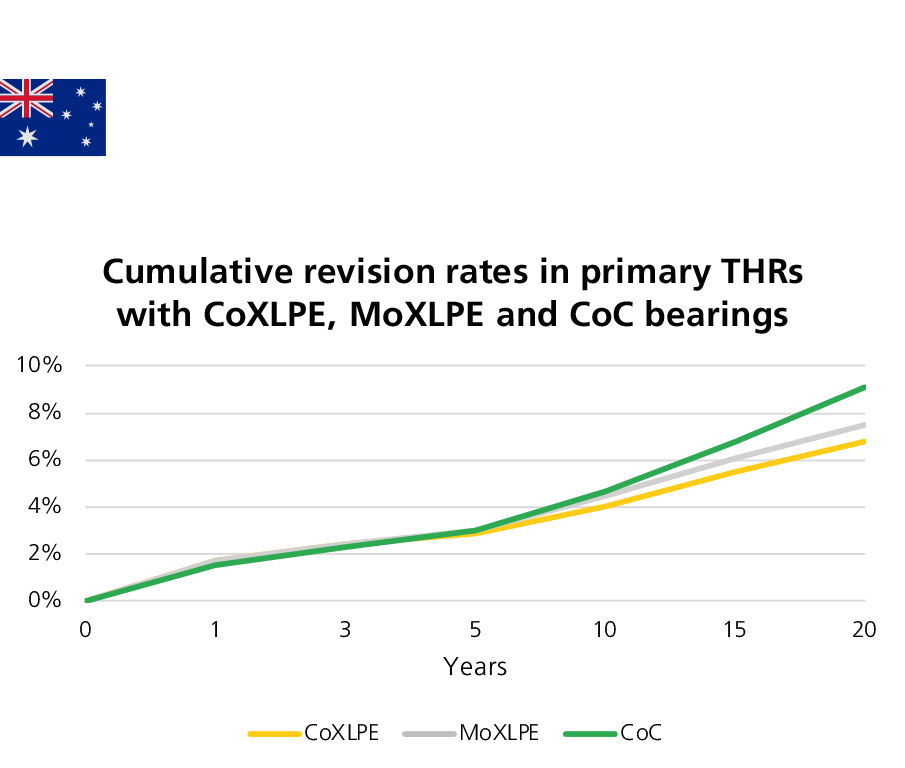

In Australia, CoXLPE shows a lower rate of revision than MoXLPE after 2 years significantly (0.77 (0.72, 0.82), p<0.001). According to the Australian registry analysis, the revision rate of CoC is not statistically different from MoXLPE at entire period (HR=0.99 (0.96,1.03), p=0.770) (Figure 18).

The lowest revision rate of revision is given by ceramicised metal heads coupled with XLPE liners, which is statistically different from MoXLPE (after 1 year: HR=0.62 (0.56,0.69), p<0.001). However, the registry urges caution in the interpretation of this result as in the previous reports since "This bearing is a single company product, used with a small number of femoral stem and acetabular component combinations. This may have a confounding effect on the outcome, making it unclear if the lower rate of revision is an effect of the bearing surface or reflects the limited combinations of femoral and acetabular prostheses."

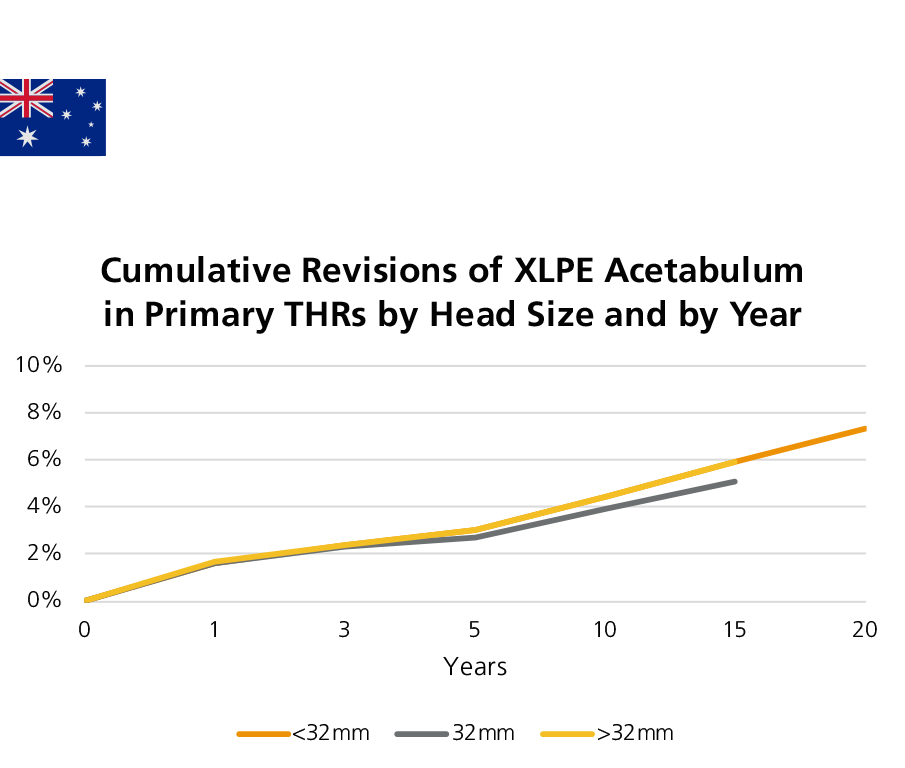

As far as the head size is concerned, the 32mm XLPE was associated with a lower rate of revision in comparison with larger heads and smaller heads (XLPE >32mm vs XLPE 32mm after one months: HR=1.13 (1.07, 1.19), p<0.001; XLPE <32mm vs XLPE 32mm after 1.5 year: HR=1.20 (1.11, 1.28), p<0.001) (Figure 19).

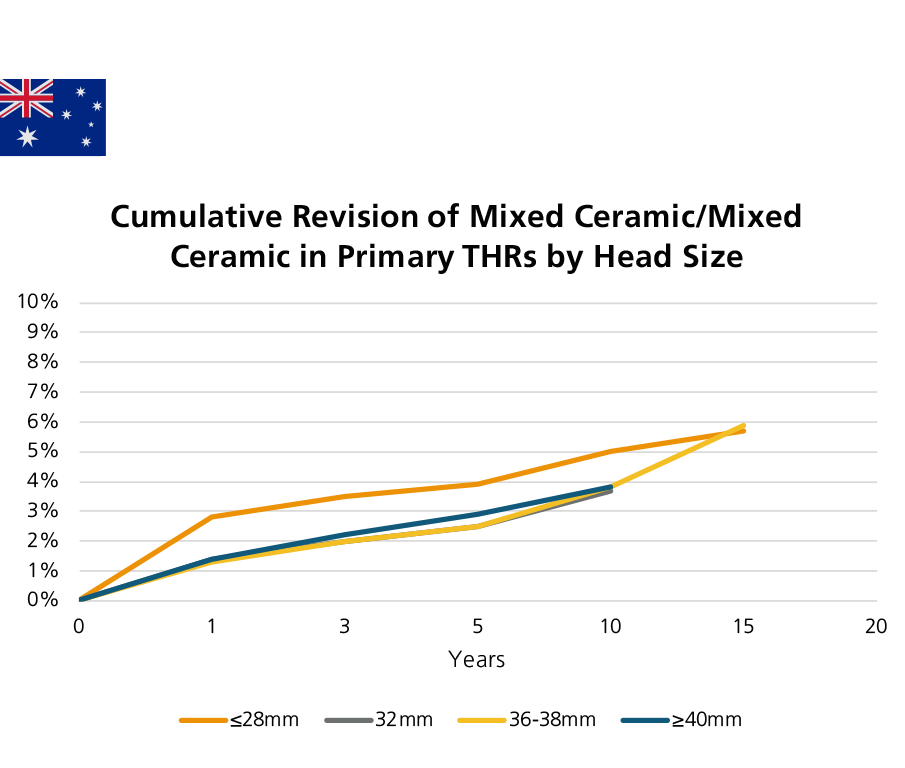

For CoC bearings with mixed ceramic (Figure 20), there is no significant difference in the rate of revision between 36-38mm and 32mm head sizes (HR=1.01 (0.88, 1.16), p=0.898). Further, also the revision rates of 36-38mm and ≥40mm head sizes are also not statistically different over the entire period (HR=0.95 (0.77, 1.17), p=0.634), also for ≥40mm versus 32mm head sizes (HR=1.06 (0.83, 1.36), p=0.632). However, the ≤28mm head sizes are associated with a higher revision rate within the first three months (HR=2.38 (1.36, 4.17), p=0.002) compared to 32mm head sizes.

Compared to XLPE + antioxidant, XLPE has a higher revision rate after 3 years (HR=1.29 (1.09, 1.53), p=0.002).

Dual mobility constructs have a lower revision for dislocation/instability compared to other acetabular prosthesis (HR=0.54 (0.41, 0.71), p<0.001). Female patients undergoing a hip procedure with a dual mobility construct have a lower rate of all cause revision compared to male (HR=0.75 (0.61, 0.92), p=0.005).

The revision rate (at 1 year) of the MatOrtho ReCerf® CoC resurfacing has been reported for the first time by the AOA NJRR in 2020. In 2022, 42 new procedures have been reported. The Australian Registry showed that the revision rate at 1 year of MatOrtho ReCerf® CoC resurfacing (0.3 (0.0, 2.1)) and at 3 years (0.3 (0.0, 2.1)), with only 1 revision of all 346 procedures, was lower than other MoM resurfacing.2

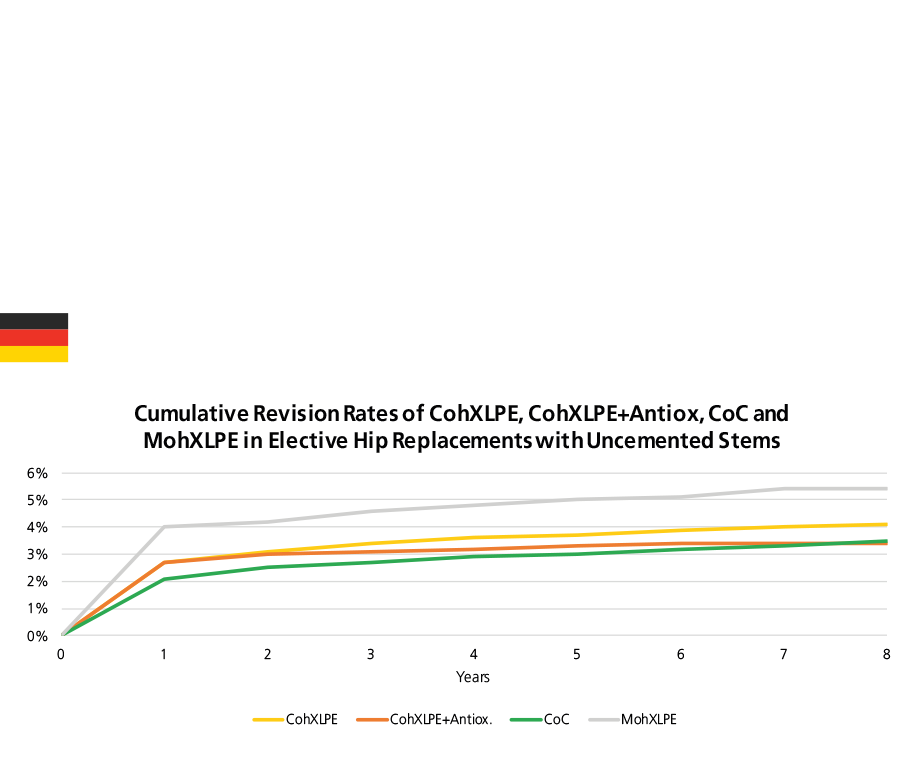

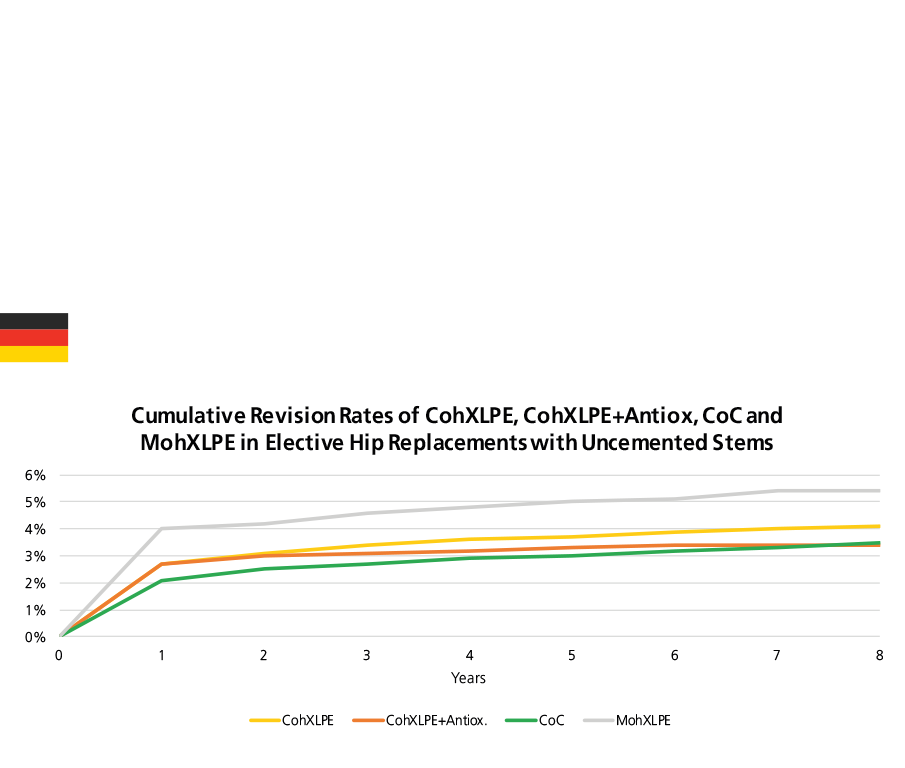

Among all bearings in elective primary THRs with uncemented stem fixation (uncemented fixation and reverse hybrid fixation), CoC had a significantly lower revision rate over the entire period than the other bearings, with the exception of CohXLPE+Antioxidants (Figure 21). Among all bearing couples in elective primary THRs, the revision rate of bearings with metal heads was significantly higher than that of bearings with ceramic heads in both cemented and uncemented stem fixation groups.

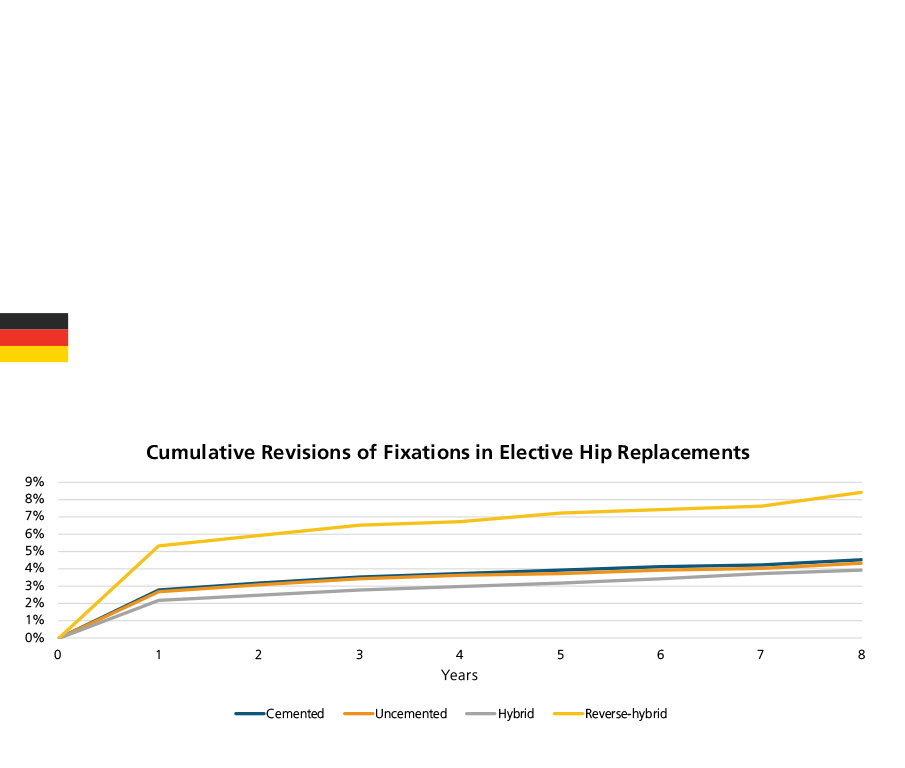

When comparing revision rates among different fixation groups, the results did not show big different between the cemented and uncemented fixation groups, which is not in line with the results observed from other registry reports (Figure 22).3

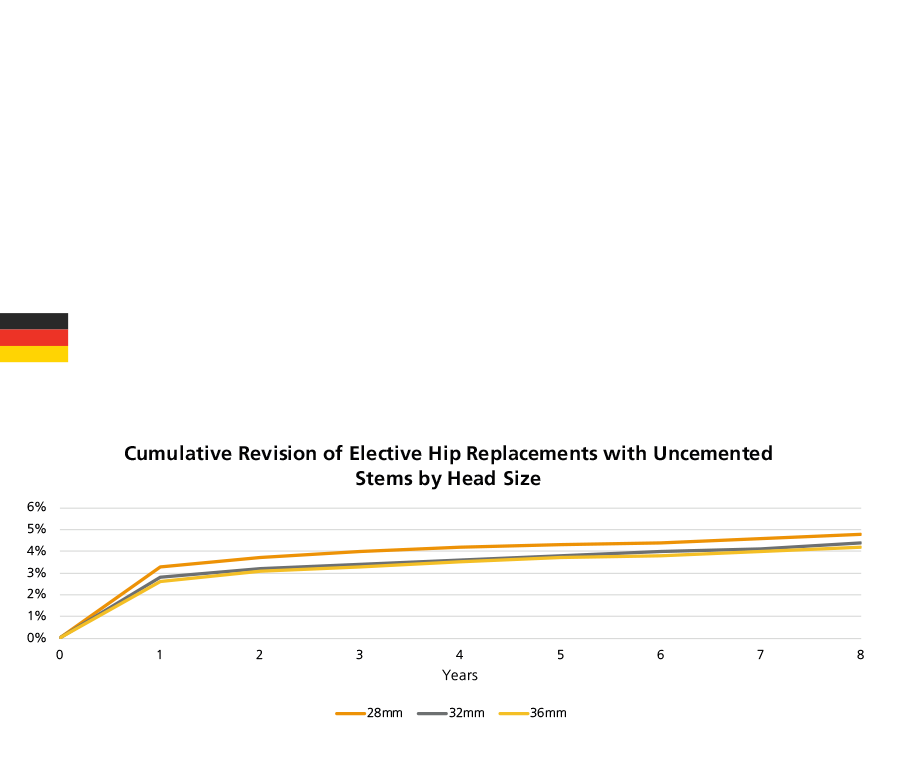

In both cemented stem fixation group and uncemented stem fixation group, 36mm head size show a lower cumulative revision rate along seven years (Figure 23).

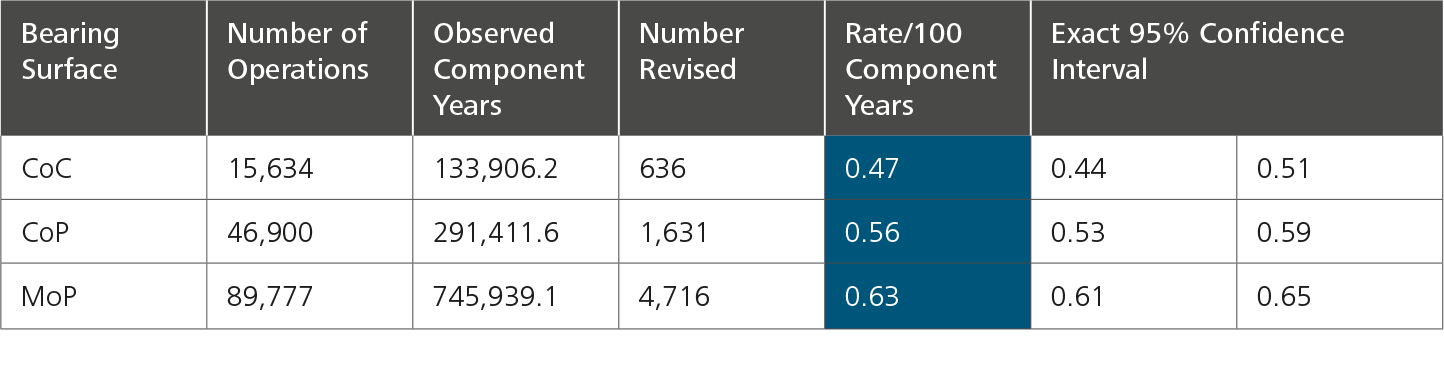

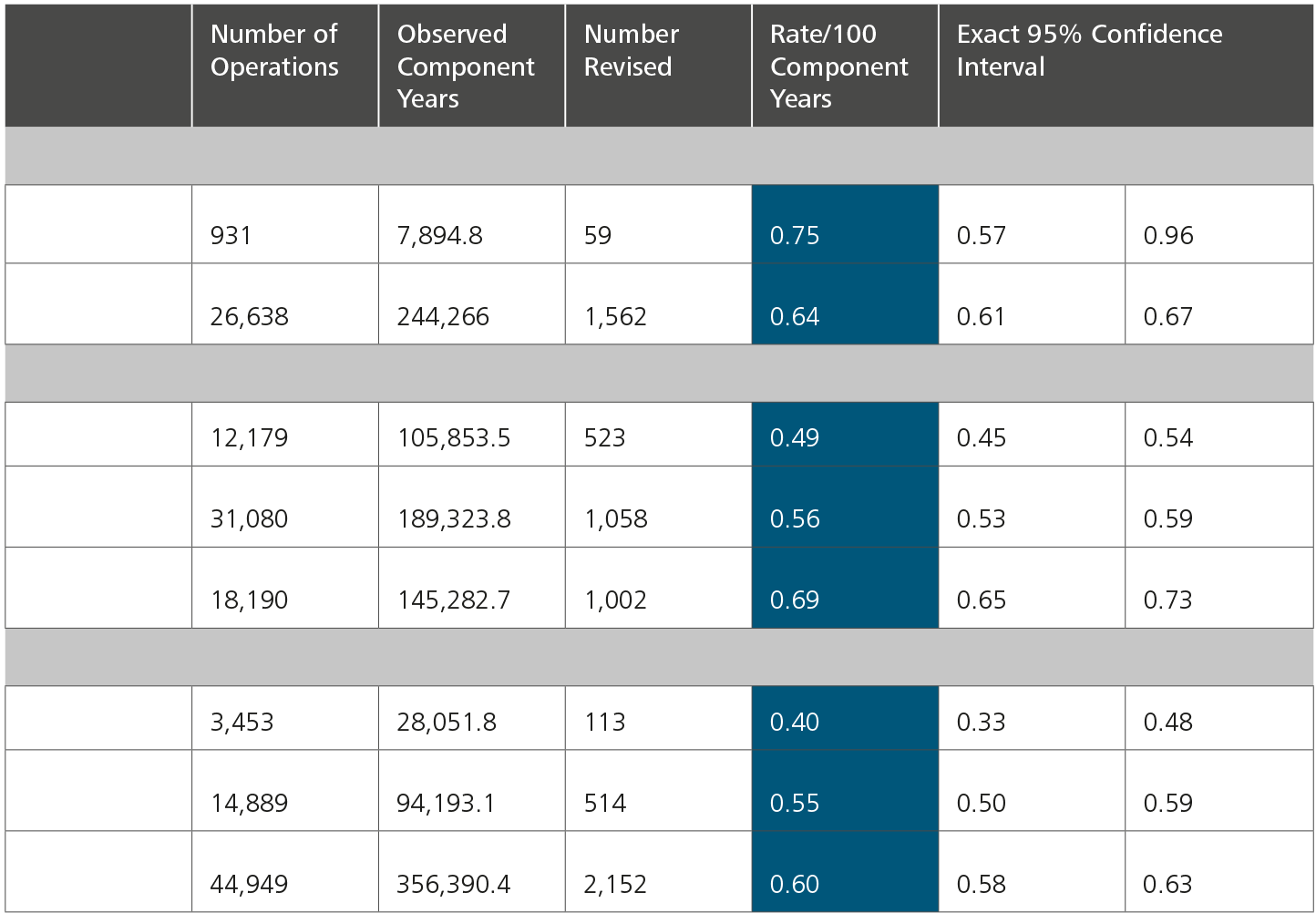

The New Zealand registry uses two very specific statistical terms for revision rates that are not found in the other registries:

Observed component years: the number of registered primary procedures multiplied by the number of years each component has been in place.

Rate/100 component years: equivalent to the yearly revision rate expressed as a percentage figure derived by dividing the number of prostheses revised by the observed component years multiplied by 100.

The NZJR shows that CoC bearings have the lowest revision rate with all head sizes in all age groups, despite the use of CoC bearings is declined.

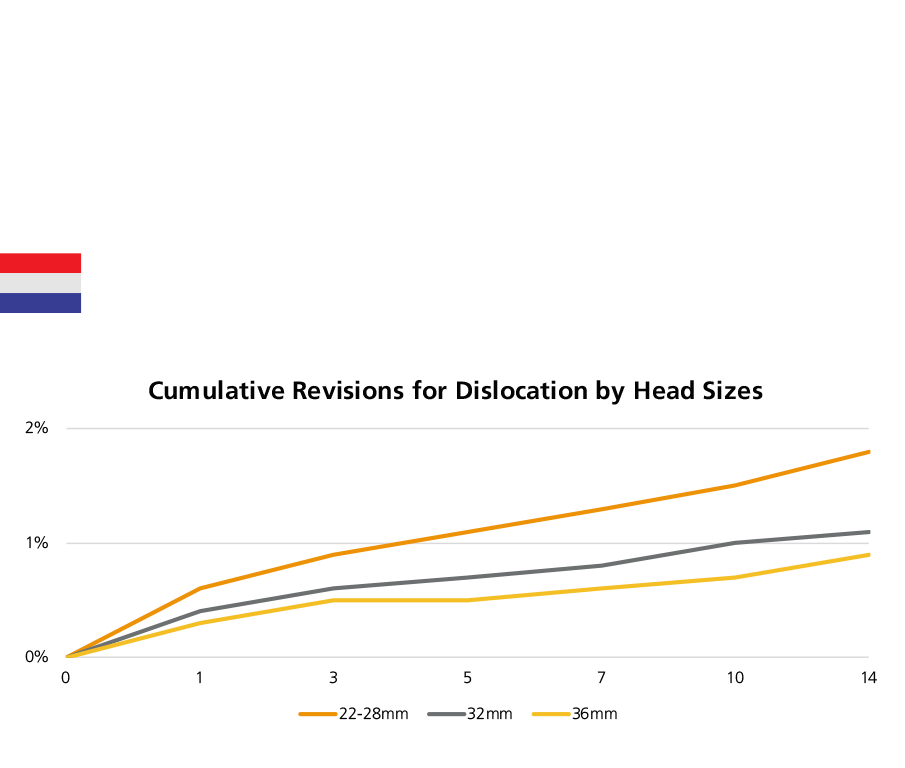

When comparing revision rate of different head size groups, in general, 32mm head size had a lower revision rate compared to the other head sizes.5

AJRR: The American Joint Replacement Registry

AOA NJRR: The Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry

CI: Confidence Interval

CMoP: Ceramicised Metal-on-Polyethylene

CoC: Ceramic-on-Ceramic

CoM: Ceramic-on-Metal

CoP: Ceramic-on-Polyethylene (including both conventional polyethylene and cross-linked polyethylene)

CoPoM: Ceramic-on-Polyethylene-on-Metal (Dual Mobility - only used by the NJR)

CoXLPE: Ceramic-on-Cross-Linked Polyethylene

CohXLPE: Ceramic-on-Highly Cross-Linked Polyethylene (only used by the EPRD)

DM: Dual Mobility

EPRD: Endoprothesenregister Deutschland (The German Arthroplasty Registry)

EQ-5D: European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions

EQ-5D-5L: European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 5 Level Version

EQ VAS Health: EuroQol-Visual Analogue Scales

HOOS JR. Score: Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score for Joint Replacement Score

HR: Hazard Ratio

ISAR: International Society of Arthroplasty Registries

MoM: Metal-on-Metal

MoP: Metal-on-Polyethylene (including both conventional polyethylene and cross-linked polyethylene)

MoPoM: Metal-on-Polyethylene-on-Metal (Dual Mobility - only used by the NJR)

MoXLPE: Metal-on-Cross-Linked Polyethylene

MohXLPE: Metal-on-Highly Cross-Linked Polyethylene (only used by the EPRD)

NHS: The National Health Service

NJR: The National Joint Registry, which covers England, Wales, Northern Ireland, the Isle of Man and the States

of Guernsey

NZJR: The New Zealand Joint Registry

OA: Osteoarthritis

PROMs: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

PROMIS-10: Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-10

SAR: The Swedish Arthroplasty Register (Merger of the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register and the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register)

SD: Standard Deviation

THA: Total Hip Arthroplasty

THR: Total Hip Replacement

VR-12: The Veterans RAND 12 Item Health Survey

Figure 12: The most common reasons for revision in England, Wales, Northern Ireland, the Isle of Man and Guernsey, Australia, the USA and the Netherlands.

Figure 13: Reasons for revision by year in Germany.

Figure 14: Reasons for revision by year in the Netherlands.

Figure 15: Reasons for revision by year in New Zealand.

Figure 16: Cumulative revision rates in primary hip replacement with Mop, CoP, and CoC bearings in combination with different fixation methods in England, Wales, Northern Ireland, the Isle of Man and Guernsey.

Figure 17: Cumulative revision rates in primary THR with CoXLPE, MoXLPE and CoC bearings (Primary Diagnosis OA) in Australia.

Figure 18: Cumulative revision rates of XLPE acetabulum in primary THR by head size (Primary Diagnosis OA, restricted to modern prostheses).

Figure 19: Cumulative revision of mixed ceramic/mixed ceramic bearings (Primary Diagnosis OA, restricted to modern prostheses) by head size in Australia.

Figure 20: Cumulative revision rates of CohXLPE, CohXLPE+Antiox, MohXLPE and CoC in elective hip replacement by stem fixation in Germany.

Figure 21: Cumulative revision rates of different fixations in elective hip replacement in Germany.

Figure 22: Cumulative revision rates of head size in elective hip replacement with different fixations in Germany.

Figure 23: Revision burden of elective primary THRs.

Table 2: Revision data by bearing type in New Zealand.

Table 3: Revision data by bearing type in New Zealand when adjusted to fixation.

References

National Joint Registry. 20th Annual Report 2023. Surgical data to 31 December 2022. ISSN 2054-183X (Online). 2023:1-370.

Smith PN, Gill DR, McAuliffe MJ, McDougall C, Stoney JD, Vertullo CJ, Wall CJ, Corfield S, Page R, Cuthbert AR, Du P, Harries D, Holder C, Lorimer MF, Cashman K, Lewis PL. Hip, Knee and Shoulder Arthroplasty: 2023 Annual Report, Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry, AOA: Adelaide, South Australia. 2023. https://doi.org/10.25310/YWQZ9375

Endoprothesenregister Deutschland (EPRD). Jahresbericht 2023. Mit Sicherheit mehr Qualität. ISBN: 978-3-949872-02-0. 2023:1-196.

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). American Joint Replacement Registry (AJRR): 2023 Annual Report. ISSN 2375-9119 (Online). 2023: 1-125.

The New Zealand Joint Registry. Twenty-four Year Report January 1999 to December 2022. 2023:1-211.

Swedish Arthroplasty Register. Annual report 2023. ISSN 16454-5982. 2023: 1-310.

Dutch Arthroplasty Register (LROI). Online LROI annual report 2023. Joint arthroplasty data to 31 December 2022. 2023: 1-249.

Endoprothesenregister Deutschland (EPRD). Statusbericht 2014 Mit Sicherheit mehr Qualität. 2015: 1-60.

Endoprothesenregister Deutschland (EPRD). Jahresbericht 2015 Mit Sicherheit mehr Qualität. ISBN: 978-3-9817673-1-5. 2016: 1-65.

Endoprothesenregister Deutschland (EPRD). Jahresbericht 2016 Mit Sicherheit mehr Qualität. 2017: 1-64.

Endoprothesenregister Deutschland (EPRD). Jahresbericht 2017 Mit Sicherheit mehr Qualität. ISBN: 978-3-9817673-3-9. 2018: 1-80.

German Arthroplasty Registry (EPRD). 2019 Annual Report. 2020: 1-125. doi:10.36186/reporteprd01202.

Endoprothesenregister Deutschland (EPRD). Jahresbericht 2020 Mit Sicherheit mehr Qualität. 2020: 1-128. doi:10.36186/reporteprd022020.

Endoprothesenregister Deutschland (EPRD). Jahresbericht 2021 Mit Sicherheit mehr Qualität. ISBN: 978-3-9817673-9-1 2021: 1-193.

Endoprothesenregister Deutschland (EPRD). Jahresbericht 2022. Mit Sicherheit mehr Qualität. ISBN: 978-3-949872-00-6 2022:1-175.